Malayalam Poetry Today: Part 1

The history of modern Malayalam poetry is a narrative of continuous innovation, gradual emancipation from the formalistic grip of traditional Sanskrit poetic practice, growing awareness of contemporary social issues and the ongoing democratization of the genre in thematic as well as formal aspects. In the process, paradigms have been tried and abandoned, communities imagined and dissolved, traditions constructed and deconstructed, the concepts of the region and the nation alternately tried out, the impact of foreign literatures absorbed and transcended, the classical and the folk heritage explored one after the other, fresh genres and formal devices employed and indigenized and the concept of the avant-garde transformed from one generation to the next.. Only in the twentieth century did Malayalam poetry become truly contemporary with the life, thought and vision of the Malayalee. For the first time it began to reflect the his /her traumatised subjectivity with its morbidity, death-wish, schizophrenia, suppressed desire and subversiveness, all of which are perhaps the wounds and traces of that fast and disturbing transformation of Kerala’s society from a tribal community to a modern civil society. More than any other genre in Malayalam literature, poetry has articulated the profound contradictions of the Malayalee psyche, its moral trepidations and its desire for liberation from the oppressive ideologies of discrimination like those of class, caste and gender. Poetry has insistently refused to be a mere entertainer or a leisure-pastime, involving itself seriously in social struggles and sharing the agonies and aspirations of individuals of all social layers and persuasions. This is also the reason for its unique vibrancy and popularity that we seldom find in most other languages of India.

Malayalam poetry’s turn towards the contemporary everyday- after its folk phase- may be said to have begun with the emergence of a poet like Kumaran Asan (1873-1924). He was a typical product of that self-criticism of the feudal Malayalee society that has been termed the Kerala Renaissance. The spread of modern education, the codification of grammar, the growth of prose genres like novel, short story, drama and essay, translations of the Bible, of Shakespeare and of Sanskrit and Tamil classics, the emergence of the printing press, the new network of newspapers and periodicals including literary ones, the introduction of science and technology, the social reform movements initiated by Sree Narayana Guru, Doctor Palpu, Chattampi Swamikal, V.T. Bhatta thirippad, Premji, Ayyankali, Sahodaran Ayyappan and others, the rise of the marginalized sections of the society to democratic awareness, the spread of egalitarian ideas, anti-colonial and anti-feudal social movements, the literacy and public library movements: all these led to a complete reordering of society and its scale of values and to the emergence of a public sphere in culture and literature.. The dividing practices that concealed inequality and exploitation behind the masks of the natural and the providential now became visible and came to be identified in their inhuman shapes. The success of someone like Sree Narayana Guru who was also a poet besides being a philosopher and reformer lay in his recognition of the relationship of discourse to power, his subtle reversal of the significance of the oppressor’s legitimizing discourse through a secular reading of their sacred texts and a subversive use of their signs, symbols and images to liberate the body from its caste marks and to de-privilege the ‘upper’ castes by revealing the illusory nature of caste divisions within the species. Kumaran Asan had learnt his philosophy partly from the Guru and partly from the Tamil Siddhas who had inspired he Guru and partly from Buddhist texts. Asan who had started as a meditative poet soon matured into a meditative poet with a deep moral and spiritual commitment. His elegy, Oru Veena Poovu ( A Fallen Flower), with its dual emphasis on the glory of the flower and the transience of its beauty became a preface to his later poems of love and compassion. His dramatic narrative poems set often in the wilderness interrogated the values of the status-quo, its concept of an all-too-physical love, its patriarchal ordering of society, the demeaning system of caste and the oppressive concept of sin without redemption. His poems like Nalini, Leela, Chandalabhikshuki and Karuna were explorations of the self in its relationship to others and the world while his Chintavishtayaya Seeta (Seeta’s Lament) where Sita interrogates the ethics of Rama who had abandoned her, a to-be mother, in the forest is a critique of patriarchal justice and the Indian concept of an ideal man and king. Asan’s Duravastha (The Sad Plight) where a Brahmin woman,Savitri, falls in love with Chathan, a dalit youth, is a direct critique of the unreal and inhuman category of caste. Asan himself was apparently apologetic about the poetic quality of this long narrative and traditional critics failed to grasp the irony in his apology. Only recently did the poet-critic Ayyappa Paniker point to the irony in Asan’s statement which was actually a challenge to the existing concept of ahistorical poetry. Paniker considers Duravastha to be the forerunner of dalit poetry in Malayalam. What survive in Kumaran Asan are the egalitarian philosopher, the great painter of exotic visuals and the interpreter of the soul in its search for peace and liberty. Vallathol Narayana Menon, his contemporary who survived him, has been noted for his felicity of phrase, sure hold on word music, dexterity in the creation of characters and commitment to the ideal of freedom and nationhood as revelaed in his narrative poems based on Hindu and Christian legends like Sishyanum Makanum ( The Disciple and the Son), Acchanum Makalum (The Father and the Daughter) and Magdalana Mariam ( Mary Magdalene) and his lyrical poems collected in the series, Sahityamanjari ( A Literary Bouquet). Ulloor Parameswara Iyer who was more of a scholar and literary historian than a poet is known for his tales of metamorphosis like Pingala and Karnabhooshanam (Karna’s Ornament) and his popular celebration of equality, Premasangeetam (The Song of Universal Love).

Changampuzha Krishna Pillai who fits the description of a typical anarchist romantic poet brought about a stylistic revolution in Malayalam poetry bringing into it the distilled essence of the folk idiom while retaining his hold on the classical vocabulary. Love and death were his central themes, nature providing a sympathetic background for the human drama as in his popular pastoral elegy, Ramanan. His short lyrical poems are also passionate and sonorous if most often melancholic. His Padunna Pisachu (The Devil Who Sings) with its overpowering sense of evil, its sense of alienation, its surrealistic imagery and its irony and self-ridicule articulates the traumatic Baudelairean ambivalence of modernity. That the Jeevatsahitya ( Progressive) movement could not reduce his influence is evident from the style of the progressives poets in Malayalam, especially the trio, Vayalar Ramavarma, P. Bhaskaran and O. N. V. Kurup, whose lyrical skill is seen also in the songs they composed for the theatre and cinema. The really important poets after Changampuzha were however another trio, Vailoppilly Sreedhara Menon, Idassery Govindan Nair and P. Kunhiraman Nair. The impact of the progressive movement was felt better in the first two of these poets than the ‘official’ representatives of the movement who did little to innovate the poetic idiom and seldom addressed the complexities of post-colonial existence. Vailoppilly’s poems like Mala Thurakkunnavar (The Tunnel-diggers), Assam Panikkar ( The Workers in Assam) and Onappattukar ( The Singers of Onam) reveal the poet’s identification with the toilers and his dreams for a just world while his Kudiyozhikkal ( The Eviction ) is one of the greatest poems in the language with its critical self-examination of the middle class and its profound grasp of the constructive and destructive aspects of the revolution. Vailoppilly could also write careful subjective poems like Kanneerpadam (The Field of Tears) and psychoanalytical works like Sahyante Makan ( Mount Sahya’s Son) where he deals with a tamed elephant’s dream of freedom in his native wilderness that drives him mad. Idassery looked at Kerala’s changing reality from the point of view of the enlightened farmer. His radical political sympathies found expression in poems like Panimudakku ( The Strike) and Puthankalavum Arivalum( The New Jar and the Sickle) while his empathy with suffering women is evident in Pengal ( The Sister) and Nellukuthukari Paruvinte Katha( The Story of Paru, the Rice-Maker). Poothappattu (The Song of the Pootham) summed up his vision of life: The pootham, the masked ritual dancer, in the poem is nature, death, the suppressed desire for motherhood and the past’s presence in the present while the mother whose child the pootham demands represents life, sacrifice, maternal intimacy and the ultimate mercy that redeems the pootham of her evil and invites her to eternal life. P. Kunhiraman Nair was the voice of memory that rebelled against the cultural amnesia brought about by colonialism and bemoaned the loss of native culture and of natural landscape occasioned by the rise of the new urban culture. G.Sankarakurup, the first Jnanpith winner now remembered mostly for his unique translations of Tagore, was a fine craftsman in verse who handled with ease cosmic themes in a high-classical style as in Viswadarsanam (The Cosmic Vision) or Sargasangeetam ( The Music of Creation) and rustic narratives in a near-folk idiom as in Chandanakkattil ( The Sandalwood Cot) or Moonaruviyum Oru Puzhayum. (Three Streams and a River). N.V.Krishna Warrier brought a new realism into poetry as in his poem Kochuthomman. Olappamanna and Akkittam with their idealism and sympathetic understanding of the plight of their class, M.Govindan with his radical social awareness, G.Kumarapillai with his lyrical skill to express moods and colours in their subtlety were also important poets of the period. Of the women poets, Balamani Amma with her intense moral anxieties expressed in her deftly crafted dramatic monologues and moving lyrics and Sugathakumari with her profound sympathy for the suffering woman, her ecological awareness, mundane spirituality and evocative lyricism are the important women poets of this period of transition and stand between the tradition of Vallathol and the new poetry that emerged almost as a movement in the 1960s.

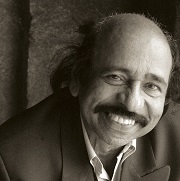

K. Sachidanandan is an Indian poet and critic writing in Malayalam and English. A pioneer of modern poetry in Malayalam, a bilingual literary critic, playwright, editor, columnist and translator, he is the former Editor of Indian Literature journal and the former Secretary of Sahitya Akademi. He is also a public intellectual of repute upholding secular anti-caste views, supporting causes like environment, human rights and free software and a well-known speaker on issues concerning contemporary Indian literature.