Malayalam Poetry Today: Part 2

The modernists of the 60s had almost all been born in the villages and moved to towns and cities in search of a livelihood. The gradual deadening of progressive sensibilities, the dogmatism of Kerala’s Left orthodoxy that led to an exclusive approach estranging from the Progressive Movement most of the writers except those who faithfully toed the party line, the new revelations about Stalin’s regime, the disappearance of Gandhian values from public life, the alienation of the thinking individual from the urban mass, an ambivalent approach to the modern experience, discontent with the existing forms and styles of poetry that seemed inadequate to express the complex experience of the times, growing acquaintance with the creative experiments in poetry in India as well as abroad: these were some of the premises of the modernist poetry of the sixties. The despair, irony and anger of Ayyappa Paniker, N.N. Kakkad, Madhavan Ayyappath, M.N. Paloor, Attoor Ravivarma, Vishnu Narayanan Namboodiri, R. Ramachandran, Cheriyan K.Cheriyan, Satchidanandan and other poets of this stream came from their lack of faith in the establishment. It was to express the structures of their modern subjectivity that they employed strategies like fantasy, surrealism, foregrounding of the signifier, Dadaist games with words and letters, irony, black humour, the use of diverse masks, alternating metaphoric and metonymic modes, re-visioning of myths and archetypes, mixing of verse and prose, redeployment of folk elements, experimental syntax and tonal variations. Language was now looked upon more as a medium of self-discovery/recovery than self-expression where the self is assumed to be known and pre-exists language. The new poets negated ossified linguistic habits and the stereotypes of instrumental rationality: the social here was the definite negation of a definite society. The very institution of literature was subjected to criticism by the new avant-garde.

Ayyappa Paniker was in a sense the epitome of all that modernism in Malayalam stood for. He introduced new forms like the cartoon poem, the sequence poem, and the ballet and drew from a variety of metrical resources, using for example the mallika metre used in the Parayan Thullal dance and the dandaka verse form used in Kathakali texts besides varieties of prose registers. His polyphonic poetry looks like an orchestra with many pieces. Touched by him, traditions no more remained the same. He wounded the unrelieved gravity of the romantics with satire and invective. He also used his black humour to critique social institutions like caste and maladies like hypocrisy, corruption, insularity and craving for material power. His more serious works like Kurukshetram, Mrityupooja (A Hymn to Death), Kudumbapuranam (The Family Saga), Pakalukal –Ratrikal (Days, Nights), Passage to America, Ivide Jeevitam ( Here, Life) Gotrayanam ( The Clan’s Progress) and Pathumanippookkal ( Ten O’Clock Flowers) reveal a deep sense of the paradoxes of life and the drama they generate.. Kurukshetram (1960) that is believed to have found the right idiom for the expression of the dilemma of the modern poses the question of justice quoting Dhritarashtra in the Mahabharata. The Bhagavatgeeta freezes and fails to to satisfy the living hour when the gods have gone to sleep and ideologies have failed man adding to the cacophony of the world’s discourse. The surreal image of the market place where “the bones eat the marrow” and “the skin preys on the bones” is central to the poem as it expresses not only the poet’s antagonism to the Luciferean city, but his revolt against the brutal mirage of the capitalist world that turns men into commodities with its Midas gaze and decomposes human consciousness in a flux of perpetual agony. The poet finds his final solace in the inner illumination, of being reborn in our dreams. N.N. Kakkad’s poems like 1963, Theerthatanam (The Pilgrimage) and Parkkil ( In the Park) are also reflections on our fragmented identities in a strife-torn world and the overarching evil that rules the modern world. Attoor Ravivarma identifies himself with the exiled hero of Kalidasa’a Meghadootam in the poem, Nagarattil oru Yakshan ( A Yaksha in the City) while Vishnu Narayanan gets panicky as he finds that the people in a festival procession drawn by his painter-friend have no faces and overhears the leaders of a demonstration whisper to one another, “Where is your face, where is yours?”. Then the poet himself rushes to the mirror to discover that he too has no face above his shirt collar. ( Mukham Evide, Where is the face?) M.N. Paloor finds his god to be a Sultan smoking his hookah filled with dried human lives ( Pedithondan, The Coward). He finds the poet of his times caught between Boeings and Comets subsisting entirely on anacin (Vimanattavalattil oru Kavi, A Poet at the Airport). Madhavan Ayyappath compares himself to a trembling solitary man perched on a hill of corpses, trying to turn the hands of a clock backward. (Maniyarayil, In the Bridal Chamber).Cheriyan finds life to be a redundant bore (Jeevitam enna Boru, A Bore called Life).

The poets of the Sixties discovered a new idiom to express the new subjectivity in the making. M.Govindan used sinewy rhythms and the alliterative syntax and the pithy style of Malayalam proverbs and riddles to move along the precarious borderland of meaning and nonsense (eg. “The foresaken leopard ate a bundle of grass; the sterile cow on seeing this devoured the bull”);Ayyappa Paniker played with words and used irony ( eg; “Didn’t you call me a robber when I am merely a thief?”, “Who would cook the Vedic lore? Are we to fry it with mustard?”); Kunjunny’s limerick-like poems laughed at the hollow men of our times and the institutions they have built (eg; “My son should learn English from the moment of his birth, and so I had my wife’s delivery arranged I England”); Madhavan Ayyappath turned poetry into a collage of quotations and used prose and verse interspersed with passages in English and Sanskrit. Kadammanitta used simple rhythms akin to the folklore.

In the Seventies, the quest for individual identity gave way to that for a socio-political identity and modern poetry got politicized. The growth of a new Maoist left I Kerala, the dalit and Bandaya Movements in states like Maharashtra and Karnataka, the all India strikes of port and railway workers, the revolts of the landless peasants and adivasis in Naxalbari , Srikakaulam and Bhojpur, women’s movements for emancipation from patriarchy, the political turbulence in African and Latin American countries, the students’ rebellion in France, the impact of Maoist thought- all these served as an impetus to a paradigmatic change. Aong with this came the discovery of a parallel political tradition in modernist poetry represented by poets like Mayakovsky, Bertolt Brecht, Martin Enzensberger, Paul Eluard, Louis Aragon, Nazim Hikmet, Nizar Khabbani, Mahmood Darwish, Lorca, Pablo Neruda, Nicolas Guillen, Davis Diop, Wole Soyinka, Aime Cesaire , Leopold Senghor and several others a lot of whose poetry was translated in the decade chiefly by K.Satchidanandan along with Kadammanitta, Ayyappa Paniker, K.G.Sankara Pillai and others. Indian poets like Sri Sri, Bishnu Dey, Subhash Mukhopadhyay, P. Lankesh, Namdeo Dhasal etc also came to be known during this time. A third world modernism seemed to be on the anvil, inspired by Nicanor Parra’s concept of ‘anti-poetry’ and Neruda’s concept of ‘impure poetry’. The pioneers of the transformation were, by general admission, K. Satchidanandan and K. G. SankaraPillai. though several poets contributed to the new spring including older poets like Attoor Ravivarma and Kadammanitta and younger poets like Civic Chandran, Sanal Das and P. Udayabhanu. K. G. Sankara Pillai’s Bengal , like Ayyappa Paniker’s Kurukshetram took off from the Mahabharata; only here the war turns into a metaphor for armed class struggle, Dhritarashtra representing the blinded hegemonic classes unable to gauge the new turns of events and haunted by the nightmares of an imminent overthrow: “This burning summer fills me with a strange fear. Even with a slight wind the dry leaves will roar and rise… and the cyclone, unawares, will rise and crush the mountains that block its way”. While the poem is ostensibly about the impending revolution, it has a subtext that is critical of the earlier ‘high modernist’ view of things as Dhritarashtra speaks of the ‘blind singers of the wasteland,’ ‘the sycophants of Death’, startled by the cyclone and refers to Sanjaya’s speech exhorting young poets to turn their poems into torches and stab the rulers with them in their faces.

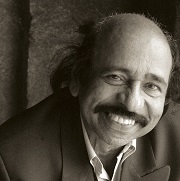

K. Sachidanandan is an Indian poet and critic writing in Malayalam and English. A pioneer of modern poetry in Malayalam, a bilingual literary critic, playwright, editor, columnist and translator, he is the former Editor of Indian Literature journal and the former Secretary of Sahitya Akademi. He is also a public intellectual of repute upholding secular anti-caste views, supporting causes like environment, human rights and free software and a well-known speaker on issues concerning contemporary Indian literature.