In Between The Finite and The Abstract

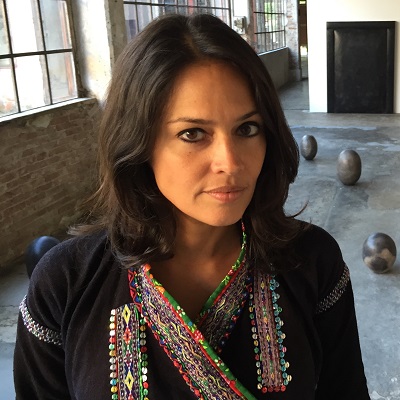

The ILF Samanvay 2015 seeks to explore the work of the creative individual with language as a transverbal medium, spanning across literature, philosophy, music and the visual and performing arts. Writer, Dancer and Poet Tishani Doshi inhabits this liminal space to breathe life into her multifaceted body of work. She has published six books of poetry and fiction to wide acclaim.

Her first book Countries of the Body won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection and her debut novel The Pleasure Seekers was shortlisted for the Hindu Literary Prize and long-listed for the Orange Prize and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. Her foray into dance was brought about by her association with the legendary choreographer Chandralekha in her final work Sharira, which will also be the closing performance at the ILF Samanvay 2015. Read on as she charts her journey so far and shares her impressions of the interconnections in her creative endeavours.

Writing and Dance. I’d like you to weigh the possibilities of ‘one distinct from the other’, ‘one feeding into the other’ and ‘one mirroring the other’. Since your work allows you to access both Writing and Dance, do you view them as different and separate? Can the differences dissolve? Is there a sameness that you see in them?

If I think of my self as a pursuer, a seeker of sorts, then it would be honest to say that I have always pursued writing. There was a definite moment in my life when I decided I would become a poet. I have doggedly followed this impulse. And it has eventually become the centre of my life. Dance, on the other hand, happened. There was no seeking of it, or imagining. But once I allowed it space, it quickly elbowed its way centrestage. Once dance entered my life, there was a sense of inevitability to it. Writing is still a surprise, a question mark. How does one begin a poem, for example? Some days the question confounds me.

Dance and Writing speak to one another, of course they do. Particularly in the early years when I just began dancing and my body was changing rapidly and forcing a physicality into all aspects of life. That physicality, because it’s so visceral, so real, has a definite effect on the writing—it forces a tautness, a discipline. The other way around? It’s hard to say. Certainly, to commit oneself to poetry, to spend hours in solitude with all the fears, anxieties, complexes and sensitivities a poet is inclined towards, must have an effect on the dance. But the quality is less translatable, more abstract. Perhaps it’s to do with the imagination. There is an aloneness with writing that there isn’t with dance, at least not in my experience. I have always felt part of a collaborative effort, and a performance, the very nature of it, is something that a writer can never really experience. Walking to the centre of a dark stage where there is just a pin of light. Putting your stomach down on it. Beginning…. Perhaps yes, there is something of that when the writer looks to the blank page, but you are not doing that in front of an audience watching. You are doing that in pyjamas at your desk. You are alone with your terrors as a writer.

Language and Body. It seems to me that the two are constantly working together, affecting one another by leaving their imprints, keeping the thread of evolution running. How do they aid as tools in the process of Writing and Dance, not necessarily in the same order? Does the process of actualizing one’s thoughts and imagination into poetry or text differ from that of dance and if so, how?

They are, but there is a sense of finiteness with the body that isn’t there with language. Language is infinite in and of itself. When you are dancing, of course, you aim for this infinite quality, but you are doing it via your finite body. And there’s magic in that, because it means that even though the body is in a constant state of decline, and you are aware of its various creaks and misgivings and capitulations, it is still capable of a kind of transcendence, and it is this leap, that is mysterious and transformative. With words too, you aim for this leap, by ordering them a particular way, by shaping them—and by trying to breathe a kind of life into them.

I see the two as quite separate though, in their temperament. Dance for me is always abstraction. It is never about tring to put into words the experience or the moment, it is feeling washing over. It is never about narrativising what is happening. This of course, has to do with my particular practise with Chandralekha. But in a sense, it feels the opposite of what I try to do with writing. When I write, I’m taking abstract feelings like love, loneliness, despair, elation and trying to make these feelings concrete. Trying to steer away from the abstract and move towards the very particular. So they do mirror each other by way of opposition.

This leads me to the transmuting of one form to the other. I’m interested in understanding how from one’s reading of text emerges an entire vocabulary of dance as in Chandralekha’s choreographic work; in how the written word can inspire the dancer to charge the body with this meaning acquired through reading.

You’ve raised an interesting point about vocabulary. In truth, I have no vocabulary in dance beyond the physical presence of my breathing body. I have not been a disciple of any form of dance. I’ve studied a few years of kallaripayattu and many years of yoga, and I have always worked with my body in a sense of being an active sports person—swimming, tennis, etc, but this is not a language of dance. This merely establishes that I am someone who has some connection with my body. Chandralekha, of course, was working from strong traditions of bharatanatyam, yoga, kallari and also a strong visual tradition too—painting, sculpture, iconography, and I think these are equally important in her vocabulary as are poetry, architecture and a word she loved —“geometry.” I cannot speak to her process, of how she arrived at her choreographies, but I can only intuit that there was a connection between all these traditions that manifested in movement. So my inspirations were not text-driven at all. I was following movements that were presecribed to me, trying to make those movements my own and internalising them. And depending on the day, the season, the moment, those movements had different meanings, never fixing at a single point of reference.

In an interview you said that Chandralekha relished the idea that you were a writer than a dancer. Could you please expand on whether it was the non-dancer in you that pleased her or the writer?

Did Writing and Dance meet and intersect through the period of your collaboration? I’d like to know if your learning and working with her informed your work as a writer and poet thereafter, and if so, how.

I think it was both. She liked that I had had no training in dance so I had not learned to stand, sit, walk a particular way. My body had no fixities, if you will. Because she herself was someone who did not like categorisations of any kind, and had been at various points in her life a poet, painter, dancer, activist, she completely “got” that I was a poet, and indulged it, and encouraged it. She would warn me never to get involved in the politics of dance, which of course, there was never any real danger of. But I think it was duality that she was interested it, or multiplicity even—the idea that one need not be contained by one defining attribute. We talked a great deal about poetry and poets—I remember her directing me to a book that I’ve since carried with me, AK Ramanujan’s Speaking of Siva. I remember bringing her a beautiful edition of Shelley’s poetry from a second hand bookstore in England because of her love for “ozymandias.” Certainly, my work as a poet was influenced and informed by my interactions with Chandra. I think when you decide to “be” an artist or writer, you never quite really know what that entails, and so for me, meeting Chandra at this nascent stage, and having an understanding of what that artistic life requires and demands of you was crucial. My first two collections of poetry were dedicated to Chandra, because in way, she was so present in the work. The concerns were of the body, but also those absract emotions we were exploring in the dance theatre—power, femininity, love, the eternal.

In a talk of yours you describe how slowness underpinned your work on Sharira and you speak of the rehearsal in silence, in effect, requiring the dancer to set the time. You also speak of how ‘going away’ helps you in your writing, in that there is a physical change and time has expanded. Stemming from this I’d like you to expand on the importance of time and place in your Writing and Dance. How do you see the Time-Space dynamic in your process as a Dancer with relation to that as a Writer and Poet? Is there a sameness or are do you see them apart from one another?

Even within the auteur’s grand vision of the piece could you find your own space to explore and assert your person and your identity? If so, could this be likened to the sense of agency and creative liberty you have in your own writing?

Both are hinting towards a sense of timelessness. But how do you use time to arrive at that state of timelessness? I am by nature an impatient person and it has been the greatest lesson, (a work in progress I might add) to understand the quality and nature of slowness, and to be able to see its powers. I think within the context of dance, I certainly had my space to explore that idea, not to say that I succeeded because the body weighs you down, and no matter how much lightness you aspire to, there’s a feeling that you are not quite transcending. There are days when something happens and you know that you have arrived there, and it is a feeling of pure exhiliration. Writing too is a Sisyphian struggle, pushing that rock up a mountain, through that heaviness trying to arrive at something weightless and eternal. Sometimes it happens effortlessly. Mostly it is a very very very slow process.

I want to extend the question of time, especially in Dance; does the dancer expand even within the ephemerality of a moment’s push, pull or slide? Because I remember after viewing a recording of Sharira, there were several such moments that were extremely powerful yet so slight and subtle that left such an indelible mark on my imagination, that I can’t exactly piece together visually or verbally now, but that feeling stays with me. And sometimes I think after witnessing something so intense and fleeting, one is trying to process this feeling of bodily engagement through words, thoughts in one’s own capacity. Are there words that people have shared with you after a performance that have stayed with you?

Yes, there are things people have said, and I wish I remembered them or wrote them down. Often, after a performance I am infused with a kind of euphoria, and of course, relief, that I’m not really cognizant of what’s going on around me. It is all feeling. But some conversations do stay. I remember someone telling me, after watching Sharira, that it was like falling in love. Someone else said, he felt his soul shooting out of his spine. Someone else just cried and could not stop crying. But you see, these are human abstractions again. One person’s falling in love is not another person’s…. and that’s what I love about this piece, it’s open-endedness….It has so many doorways through which to enter it….. You mentioned those minute moments, the ephemera contained within a small movement, and I think that’s a really important point. In music, as in poetry, those moments of silence or breath, the space between what is meant to be happening are as important as the happening itself, and it’s those moments between movements, when one thing slides into another, that fascinate me, and I think that make us shiver a little because there lies the mystery perhaps, the unknowing.

I think also that there is a sense of limitlessness to your writing, like for instance when I read “The Pleasure Seekers” I felt safe and enabled, to wander, reflect and reconnect with grace, beauty and innocence. Is this perhaps owing to your craft as a poet, or do you see it as a more unifying philosophy that you follow in Writing and your encounters with Language?

You want to create a universe when you’re writing. Poems are different in their sense of scale. When I am immersed in a poem I am very comprehensively in it, but it is not sustained beyond that poem. With a novel, your sense of time is completely different. You’re tunnelling, tunnelling….The time that you take to create this universe, but also the sense of time you’re creating in that universe. Poems have that sense of nowness, or immediacy about them, but to achieve that in a novel, and to have this “limitlessness” as you say —it’s really a concerted effort…

To cap it all off, how would you summarize your individual experiences as Writer, Poet and Dancer, and how you see them in relation to one another, and as a whole?

I am what I am on any given day. And if I’m lucky I can be all of them on one day.