Translation and the idea of Indian Literature: Last Part

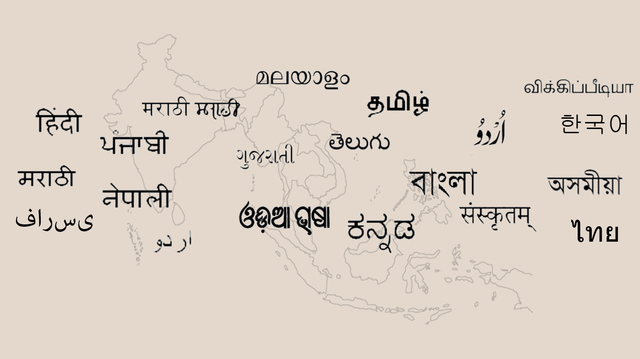

Even a brief examination of some key moments in the evolution of India’s literature is enough to prove the variety as well as the common sources and concerns of our literatures. After more than five decades of independence and five hundred years of imperial and colonial rule, it is imperative that we rethink concepts like Indianness and Indian literature. One may then be able to unveil the complicity of these concepts with the ideology of colonialism on the one hand and globalisation on the other. We have come a long way since the German romantic theorist Wilhelm von Schlegal used the term Indian literature to mean Sanskrit literature (1823) Since then many other scholars have used the term as being synonymous with Sanskrit literature, at the most extended to include Prakrit, Apabhramasa and Pali literatures. M Garcin de Tassy’s two-volume History of the Literature of of Hindu and Hindustani in French( 1839-47; later revised and enlarged as a three-volume edition in 1870-71), Albrecht Weber’s History of Indian Literature in German (1852), George A. Grierson’s Modern Vernacular Literature of Hindustan (1889), Ernst P. Horowitz’s A Short History of Indian Literature and Moriz Winternitz’s History of Indian Literature (1908-1922)in German as well as Herbert H Gowen’s History of Indian Literature (1931) have all contributed to the constitution of the category of Indian literature. Most of these do not represent, or at best underrepresent, the literatures in the modern Indian languages that were full-grown by the time and many even had their own histories of literature written in the concerned language itself. Sanskrit was posited by them as the classical code of early India, congruent with new linked conceptions of classicism and class. Indian scholars too have contributed in a big way to the constitution of the category of Indian literature though many of their approaches are more nuanced and they take into account modern languages in various ways. Sri Aurobindo, Krishna Kripalani, Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, V K Gokak, Umashankar Joshi, Sujit Mukherjee, Sisir Kumar Das, K M George, Ganesh Devy etc have elaborated the category as a posited unity of diverse language formations or as the articulation of ‘Indian Culture’. Aijaz Ahmed in his essay on Indian litearture in In Theory has acknowledged the difficulties of positing such a unitary category.

T R S Sharma has pointed to the European neglect of the Indian languages in his introduction to Ancient Indian Literature, an anthology edited by him for the Sahitya Akademi, “While many European scholars had translated entire works of Sanskrit, few of them had ventured into Prakrit and Apabhramsa and none into Kannada”. This is also true of other languages often including classical languages like Tamil.. As P. P Ravindran remarks in an article ( ‘Genealogies of Indian Literature’, Economic and Political Weekly, 24 June, 2006),

Even today European scholars of modern south Asian languages and literature feel compelled to legitimise themselves and their fields of study, working as they do in departments of south Asian studies, -at times designated even now as departments of Indology- that are dominated largely by classical Sanskrit scholars.

Pointing to the introduction of Narrative Strategies: Essays on South Asian Literature and Film by Vasudha Dalmia and Theo Damsteegt,( Leiden, 1998), where they claim to let the world know ‘the seriousness’ of their disciplne, he points out how their statement is unabashedly Eurocentric and ignorant or deliberately neglectful of the enormous scholarship that has been produced on Indian literature by scholars of various hues from the south Asian subcontinent. It is disgraceful that the attitude of European scholarship to this mighty archive remains unchanged since the 19th century. All these works also share the class and caste prejudices of the tradition of the Sanskrit-based Hindu orthodoxy. Only recently have some scholars like Sheldon Pollock begun to realize this as is evident in his introduction to from Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia ( New Delhi, 2003)where the language literatures have been treated in isolation as also in relation to other language literatures in India. Sheldon Pollock says:

“With very few exceptions, European histories of Indian literature remained histories of sanskrit and its congeners… The real plurality of literatures in south Asia and heir dynamic and long-term interaction were scarcely recognized, except perhaps incidentally by Protestant missionaries and British civil servants who were prompted by the practical objectives of conversion and control..”

Pollock also examines how the Subaltern school of historiography has sought to redirect the study of 19th and early 20th century Indian society and politics ‘toward the popular, the vernacular, the oral, and the local, and to recapture the role of small people in effecting big historical change.’

Contemporary analyses of colonialism have shown how new Indian pasts with real-life social consequences, such as the traditionalization of the social order by the systematic mis-cognition of indigenous discourses on caste were created by colonial knowledge. They have demonstrated at the same time how discourses such as Nationalism that were borrowed from Europe entered into complex interaction with local modes of thought and action that, through a process not unlike import substitution, appropriated, rejected, transformed, or replaced them.

He goes on to say how the reexamination of theory, practice and history of areas, especially driven by the analysis of globalization, has made us aware of the artificiality of geographical boundaries of inquiry.

Today we need to develop alternative genealogies that go beyond the hegemonic canon and travel to the deepest springs of popular creativity. Rather than a mechanical unitary concept we need to develop a comparative concept, a fresh literary cartography, marking areas of isolation and interaction, patterns specific to languages and influences that they share. Only then will we be able to overcome the binary opposition between the singular and the plural as irreconcilable antinomies and arrive at a dialectical concept of Indian literature in its twin aspects of unity and diversity. Translation that resists standardization being attentive to local colours, tones and textures, can play a central role in forming such a dialectical and comparative concept of Indian literature that grasps it in its twin aspects of similarity and difference, its unity and diversity.

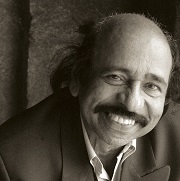

K. Sachidanandan is an Indian poet and critic writing in Malayalam and English. A pioneer of modern poetry in Malayalam, a bilingual literary critic, playwright, editor, columnist and translator, he is the former Editor of Indian Literature journal and the former Secretary of Sahitya Akademi. He is also a public intellectual of repute upholding secular anti-caste views, supporting causes like environment, human rights and free software and a well-known speaker on issues concerning contemporary Indian literature.